Memory As Resistance in Joanna Newsom’s “Sapokanikan”

Illustration depicting the Lenape village, Sapokanikan. Sourced via La Testa Magazine

A few months ago, I stumbled across a song called Sapokanikan by Joanna Newsom. I was brought to tears once I began to understand the references she was making throughout the song.

Simply put, Sapokanikan is a song about buried legacies which carries you through a very emotional journey from the past to now. In the 5-minute music video, Newsom walks through the city of New York referencing old dutch masters, cryptic records, and lost causes that were died for. By the end of the song, she is calling us to think about what the hunter from 100 years from now will decipher from the “stone”, a metaphor for the tributes that we, the modern person, will leave behind. Newsom thinks that the hunter may “look, and despair”.

The music video itself has a very moving quality. Its setting of present-day New York being juxtaposed with the call-backs made throughout the song to the people who previously inhabited the area puts the listener in a kind of existential frame of thought. The song has a way of playing on themes and counter themes like forgetting and remembering, the living and the dead, and hope and despair, that gives anyone listening no choice but to be viscerally aware of the time of their existence.

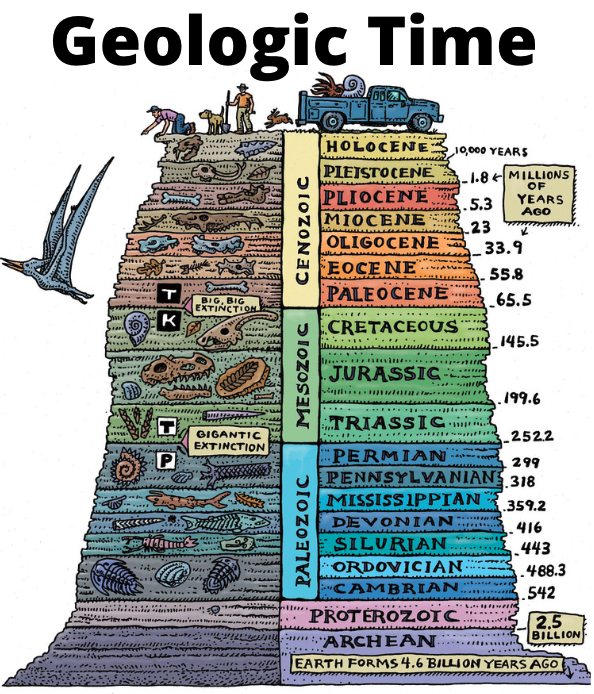

I once was told to think of time as deep, “deep time”. The deeper you go into the ground, the older that the things you will find are, and the further in the past you are, kind of like time-travelling. Think rock formations, mountain formations, the evolution of species. All are things that happen over deep time scales and that we have the ability to physically see if we examine them. Newsom’s song is like this but in reverse, starting at a point in the past deep in the ground and bringing us up to the surface, aka present day. At the end of the song we are reminded that layers will develop on top of us, and we will be the ones being “uncovered” by those on the surface as an obscure part of history.

Now I want to zoom in a bit to the name of the song, Sapokanikan. In what is now known today as Greenwich Village, was a Native American Lenape settlement called Sapokanikan (also called Saphokanican, Sappocanicon or Sappokanikee), the name roughly translates to “tobacco field” or “place where tobacco is grown”. Like other Native American tribes, the Lenape were gifted in picking out good locations for their wigwams (round houses made from wood, common in the summer), and longhouses (much larger and more permanent than wigwams, commonly used in the winter months). They had seasonal settlements, made sophisticated land use, and created a network of trails and waterways which shaped the landscape. Sapokanikan was one of these seasonal settlements.

On this island of Manhattan they had appropriated the finest, richest, yet driest piece of ground to be had. There were woods and fields; there was a marvellous tout stream (Minetta Water); there was a game preserve second to none, presented by the Great Spirit. There was pure air from the river, and a fine loamy soil for their humble crops. It was good medicine.

- Anna Alice Chapin, Greenwich Village (1917)

In Chapin’s telling of the history of Greenwich Village, Sapokanikan appears briefly as a paragraph acknowledging the Lenape settlement on Manhattan’s west side, before the door is shut with a single sentence: “But their day passed.” She then goes on to talk about Peter Minuit, who “bought” the land from the Lenape for $24 to develop spots for the Dutch West India Compan. A “thrifty deal” she adds, while describing Minuit as “a worth while man who deserved to be remembered.”

I don’t think there could be a better demonstration of how forgetting and remembering are structured by power than this passage.

Her language commodifies land by treating Manhattan as an asset to be acquired, all the while leaving out the disparities in understanding land, ownership, and consent between the Lenape and the Dutch. We know that Peter Minuit, on behalf of the Dutch West India Company, conducted what became the legendary $24 “purchase” of Manhattan from the Lenape, but now historians agree that this was a more complicated encounter. The Dutch believed they secured transferable title through the exchange, but Lenape concepts of landholding meant that the transaction didn’t reflect consent as it is understood today.

Chapin marginalises the Lenape not only by omission, but through linguistic flattening. She reduces their existence to a bygone, as if their claim to place and meaning just simply expired. In doing this, she closes the door on continuity and recasts any Indigenous presence as a completed, obsolete episode when it is actually part of a layered and contested geography. This is “history is written by the victors” personified.

The map of Sapokanikan

Is sanded and beveled

The land lone and levelled

By some unrecorded and powerful hand

- Joanna Newsom, Sapokanikan (2015)

Pierre Nora’s concept of lieux de mémoire, “sites of memory”, helps explain why someone like Minuit is “remembered” and why Sapokanikan is not. Nora theorises that memory survives where it is deliberately fixed through monuments, named places and institutional stories. Minuit gets a place in the dominant narrative (and later cultural recall) because colonial historiography invested in making him a foundational figure; the Lenape settlement, with no empowered agency in those memorialising institutions, lacks that crystallisation and so slides toward oblivion. This is all intentional, as memory is power. The irony is that while the act of remembering Minuit legitimises conquest, it also is an admission of what was done to the Lenape. There is also irony in the fading of “their day” being framed as natural rather than produced.

Beneath a patch of grass

Her bones the old Dutch master hid

While elsewhere Tobias

And the angel disguised

What the scholars surmise was a mother and kid

- Joanna Newsom, Sapokanikan (2015)

The Lenape’s settlement doesn’t survive in monuments or dominant narratives, only in faint traces like maps, etymology, and song. They are completely erased from New York’s visible commemorations. Much of Newsom’s song meditates on what survives in public memory, things like statues, monuments and names, and contrasts it with what doesn’t.

And the cause they died for are lost in the idling bird calls

And the records they left are cryptic at best

Lost in obsolescence

The text will not yield, nor x-ray reveal

With any fluorescence

Where the hand of the master begins and ends

- Joanna Newsom, Sapokanikan (2015)

Sapokanikan morphs into Greenwich Village, which morphs again into a bohemian hub, and now a gentrified neighbourhood. Each transformation further layers over the Indigenous past as Sapokanikan becomes largely forgotten, replaced by colonial and then American symbols.

Imagine an alternative telling of Sapokanikan which traces the Lenape’s seasonal cycles of fishing, farming, and trade along the Hudson, the significance of tobacco cultivation to their cultural life, and the settlement’s role within Lenapehoking’s wider network. It might name the leaders, recount oral histories, map the trails and waterways that connected Sapokanikan to other communities. It would note that, far from “passing,” the Lenape’s descendants still flourish and maintain cultural continuity despite displacement. In this version, the colonial encounter is not the pivot point to glory but a disruption in an ongoing Indigenous story. Minuit’s deal could be framed within the context of asymmetrical power and contested understandings of land, and Sapokanikan’s name might survive on street signs, in public art, and in school curricula.

It would go in hand with present-day recovery efforts like the Lenape Center’s cultural programming, New York’s slow adoption of Indigenous place-name markers, and artistic works like Joanna Newsom’s Sapokanikan. It would show how erasure was never inevitable, it was a choice, and memory can still be restructured to restore Sapokanikan’s place as a living part of the city’s identity.

Remembrance through revival keeps alive the question of who is allowed to linger in the world’s memory and who is folded into silence, a question that extends far beyond Manhattan’s history. In Palestine, as in so many places shaped by displacement, the ground itself is made to forget, villages vanish beneath new foundations, names are rewritten in another language, and maps are redrawn to close the gap between absence and amnesia. Yet, as with Indigenous recovery efforts in New York, deliberate acts of revival like documenting oral histories and creating art that insists on continuity push back against erasure. These are acts that refuse the finality of erasure by demonstrating that memory is an active site of resistance, and that even under immense pressure, it can be restructured to preserve presence, dignity, and the right to be remembered. Deliberate acts of remembering through revival prove that the measure of a people’s existence does not have to be set by the power that displaces them, it lives in the endurance of their memory.